Why Adaptation Fails in Island Systems That Cannot Rewind

Adaptation assumes something islands do not have

Adaptation is a comforting idea.

It suggests that when conditions change, systems can respond, adjust, and recover.

In many places, this is true.

In island systems like the Maldives, it is not.

The reason is not poor management or lack of intelligence.

It is structural.

Some systems cannot return to earlier states once certain changes occur.

They do not rewind.

Non-ergodicity, in plain language

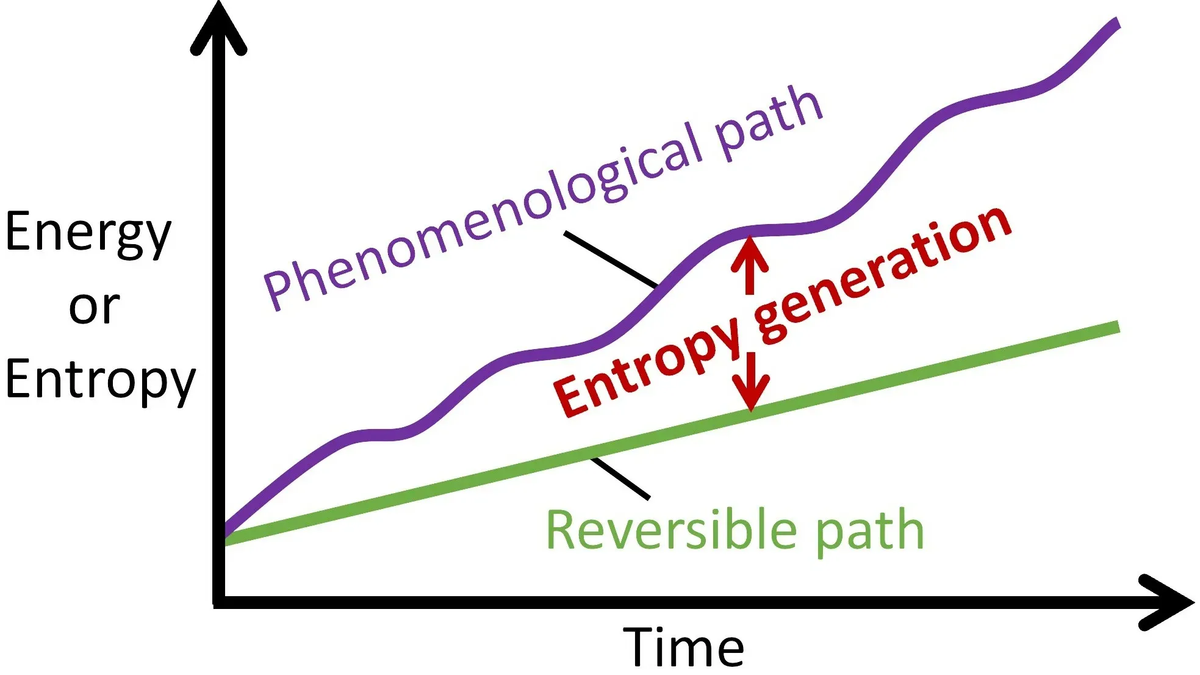

A system is ergodic if setbacks can be averaged out over time.

Losses in one period can be recovered later.

A system is non-ergodic if early outcomes permanently shape what comes next.

Islands are non-ergodic systems.

What happens first matters more than what happens later.

Because buffers are thin, space is finite, and identity is tightly coupled, some paths—once taken—cannot be undone.

Adaptation assumes reversibility.

Island reality does not offer it.

Why islands cannot rewind

Island systems fail the reversibility test for several reasons:

- Thin buffers

Financial, ecological, and institutional reserves are small. There is little slack to absorb repeated shocks. - Spatial constraint

Land, reef, lagoon, and freshwater limits are physical, not theoretical. Once repurposed or degraded, recovery is slow or impossible. - Identity coupling

Culture, labour, and place are tightly linked. When routines and roles shift, they do not reset easily. - Path dependence

Early choices shape later options. What looks like flexibility at first becomes rigidity over time.

In such systems, adaptation works only before certain thresholds are crossed—often before they are visible.

Why adaptive planning assumes too much

Adaptive planning relies on a simple sequence:

observe → confirm → adjust.

This sequence only works when:

- signals arrive early,

- adjustments are fast,

- reversibility remains available.

In non-ergodic systems, confirmation arrives late.

By the time indicators validate concern, the system has already reorganised itself around new pressures—new labour patterns, new pricing expectations, new ecological loads.

Adaptation becomes cosmetic.

Correction becomes impossible.

A quiet regime shift, not a crisis

The Maldives is not experiencing collapse.

It is experiencing a regime shift.

Recent signals illustrate this change:

- visitor arrivals continue to rise,

- average length of stay is shortening,

- value growth per visitor is moderating rather than accelerating.

None of these are alarming in isolation.

Together, they indicate a system compensating—working harder to maintain surface performance while underlying dynamics change.

This is how non-ergodic systems behave before problems become visible.

Why “we can fix it later” fails

In ergodic systems, later exists.

In island systems, it often does not.

Once:

- land is repurposed,

- labour skills drift,

- ecological pressure concentrates,

- cultural rhythms adapt to throughput,

…the option set narrows permanently.

Policy can slow decline.

It cannot restore lost states.

This is why adaptation fails—not because it is misguided, but because it arrives after the window closes.

The uncomfortable implication

If systems cannot rewind, governance must act before certainty.

Waiting for proof is rational in reversible environments.

In island systems, it is dangerous.

This does not call for panic.

It calls for humility about timing.

The most costly mistakes in non-ergodic systems are not dramatic decisions.

They are delays.

What comes next

If adaptation is structurally limited, timing—not intention—becomes the critical variable.

The next question is unavoidable:

Why do island systems consistently recognise saturation only after it has already taken hold?