Why Island Systems Detect Saturation Too Late

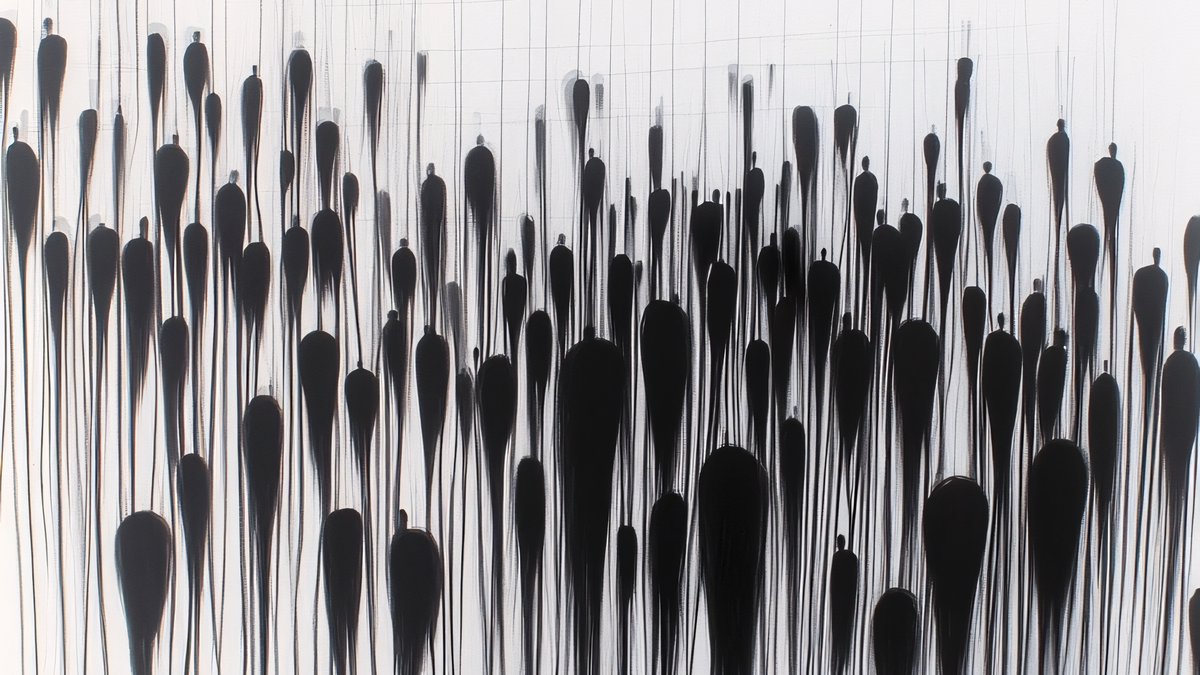

Saturation rarely announces itself

Saturation is often imagined as a clear line.

A moment when capacity is exceeded and alarms sound.

Island systems do not behave this way.

They drift.

Pressure accumulates gradually, unevenly, and quietly.

By the time saturation is officially recognised, it has usually been shaping outcomes for years.

Saturation is a process, not a threshold

In island economies, saturation does not arrive all at once.

It appears as:

- slightly shorter stays,

- slightly lower margins,

- slightly busier harbours,

- slightly higher staff turnover,

- slightly heavier waste loads,

- slightly thinner patience in shared spaces.

Each change is small enough to be explained away.

Together, they indicate a system under strain.

Because no single indicator collapses, saturation remains invisible to formal monitoring.

Indicator lag versus lived reality

Planning systems depend on indicators:

occupancy rates,

arrival numbers,

revenue totals,

employment figures.

Island life experiences saturation differently.

Residents feel it in congestion and fatigue.

Operators feel it in tighter margins and constant improvisation.

Ecosystems feel it in cumulative stress rather than sudden damage.

These signals are qualitative, distributed, and difficult to aggregate.

They arrive long before metrics confirm a problem.

Planning listens for confirmation.

Island systems communicate through drift.

The divergence that misleads decision-makers

One of the most dangerous features of saturation is divergence.

On the surface:

- arrivals grow,

- rooms fill,

- GDP rises,

- infrastructure expands.

Underneath:

- value density thins,

- buffers shrink,

- resilience erodes.

The system looks healthy because it is compensating.

It adds volume to offset declining depth.

It stretches labour to maintain service levels.

It absorbs ecological stress without immediate collapse.

This compensation delays recognition—until it can no longer continue.

Why adaptive management waits too long

Adaptive management is designed to avoid overreaction.

It waits for patterns to stabilise before intervening.

In island systems, this caution becomes a liability.

By the time data confirms saturation:

- investments are sunk,

- labour has reallocated permanently,

- pricing expectations have reset,

- ecosystems have crossed recovery limits.

The window for gentle correction has closed.

Waiting feels responsible.

In non-ergodic systems, it is often decisive—in the wrong direction.

Why waiting creates lock-in

Saturation does not only strain systems.

It reshapes them.

Once high throughput becomes normal:

- planning assumes volume,

- business models depend on it,

- political costs of reversal rise.

At that point, even acknowledging saturation becomes difficult.

The system has adapted around the very pressure it needed to prevent.

This is how lock-in forms—not through bad decisions, but through delayed ones.

The quiet danger of “still working”

Island systems are most vulnerable when they appear to function.

As long as:

- rooms are occupied,

- revenues remain positive,

- employment continues,

there is little urgency to ask deeper questions.

But “still working” is not the same as being sustainable.

In island contexts, it often means the system is consuming its remaining margin.

What saturation teaches—if noticed early

Saturation is not a failure signal.

It is a timing signal.

It tells us limits are approaching, not that collapse has arrived.

The tragedy is not that island systems saturate.

All systems do.

The tragedy is that islands recognise saturation only after reversal is no longer possible.

What comes next

If saturation is detected late, something else must already be failing.

Not demand.

Not growth.

Value.

The next step is to understand how high-value tourism erodes quietly—long before anyone calls it failure.